Ðåôåðàòû ïî àâèàöèè è êîñìîíàâòèêå

Ðåôåðàòû ïî àäìèíèñòðàòèâíîìó ïðàâó

Ðåôåðàòû ïî áåçîïàñíîñòè æèçíåäåÿòåëüíîñòè

Ðåôåðàòû ïî àðáèòðàæíîìó ïðîöåññó

Ðåôåðàòû ïî àðõèòåêòóðå

Ðåôåðàòû ïî àñòðîíîìèè

Ðåôåðàòû ïî áàíêîâñêîìó äåëó

Ðåôåðàòû ïî ñåêñîëîãèè

Ðåôåðàòû ïî èíôîðìàòèêå ïðîãðàììèðîâàíèþ

Ðåôåðàòû ïî áèîëîãèè

Ðåôåðàòû ïî ýêîíîìèêå

Ðåôåðàòû ïî ìîñêâîâåäåíèþ

Ðåôåðàòû ïî ýêîëîãèè

Êðàòêîå ñîäåðæàíèå ïðîèçâåäåíèé

Ðåôåðàòû ïî ôèçêóëüòóðå è ñïîðòó

Òîïèêè ïî àíãëèéñêîìó ÿçûêó

Ðåôåðàòû ïî ìàòåìàòèêå

Ðåôåðàòû ïî ìóçûêå

Îñòàëüíûå ðåôåðàòû

Ðåôåðàòû ïî áèðæåâîìó äåëó

Ðåôåðàòû ïî áîòàíèêå è ñåëüñêîìó õîçÿéñòâó

Ðåôåðàòû ïî áóõãàëòåðñêîìó ó÷åòó è àóäèòó

Ðåôåðàòû ïî âàëþòíûì îòíîøåíèÿì

Ðåôåðàòû ïî âåòåðèíàðèè

Ðåôåðàòû äëÿ âîåííîé êàôåäðû

Ðåôåðàòû ïî ãåîãðàôèè

Ðåôåðàòû ïî ãåîäåçèè

Ðåôåðàòû ïî ãåîëîãèè

Ðåôåðàòû ïî ãåîïîëèòèêå

Ðåôåðàòû ïî ãîñóäàðñòâó è ïðàâó

Ðåôåðàòû ïî ãðàæäàíñêîìó ïðàâó è ïðîöåññó

Ðåôåðàòû ïî êðåäèòîâàíèþ

Ðåôåðàòû ïî åñòåñòâîçíàíèþ

Ðåôåðàòû ïî èñòîðèè òåõíèêè

Ðåôåðàòû ïî æóðíàëèñòèêå

Ðåôåðàòû ïî çîîëîãèè

Ðåôåðàòû ïî èíâåñòèöèÿì

Ðåôåðàòû ïî èíôîðìàòèêå

Èñòîðè÷åñêèå ëè÷íîñòè

Ðåôåðàòû ïî êèáåðíåòèêå

Ðåôåðàòû ïî êîììóíèêàöèè è ñâÿçè

Ðåôåðàòû ïî êîñìåòîëîãèè

Ðåôåðàòû ïî êðèìèíàëèñòèêå

Ðåôåðàòû ïî êðèìèíîëîãèè

Ðåôåðàòû ïî íàóêå è òåõíèêå

Ðåôåðàòû ïî êóëèíàðèè

Ðåôåðàòû ïî êóëüòóðîëîãèè

Êóðñîâàÿ ðàáîòà: Project Work in Teaching English

Êóðñîâàÿ ðàáîòà: Project Work in Teaching English

MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE OF UKRAINE

IVAN FRANKO NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF L’VIV

COLLEGE OF EDUCATION

PROJECT WORK IN TEACHING ENGLISH

Course paper

presented by

a 4th-year student

Ivanna Linitska

Supervised by

Zadunayska Y. V.,

Teacher of English

L’VIV – 2010

Table of Contents

Introduction

Chapter I. Project Work in Teaching English

1.1 Characteristics of Project Work

1.2 Types of Project Work

1.3 Organizing Project Work

Chapter II. Examples of Project Work Activities

2.1 Project Work Activities for the Elementary Level

2.2 Project Work Activities for the Intermediate Level

2.3 Project Work Activities for the Advanced Level

Conclusions

List of References

Introduction

The theme of the course paper is “Project Work in Teaching English”.

The objectives of the paper are to highlight the importance of project work in teaching English, to describe its main peculiarities and types, to discover how it influences the students during the educational process and if it helps to learn the language.

The problem of using project work in teaching English is of great importance. Project work is characterized as one of the most effective methods of teaching and learning a foreign language through research and communication, different types of this method allow us to use it in all the spheres of the educational process. It involves multiskill activities which focus on a theme of interest rather than of specific language tasks and helps the students to develop their imagination and creativity. Nevertheless, teachers are not keen on the idea of providing project work into their lessons because of the disadvantages this method has. The main idea of project work is considered to be based on teaching students through research activities and stimulating their personal interest.

The research topic of the course paper is the process of teaching and learning a foreign language with the help of project work.

The research focus of the paper is the content of project work activities.

The research tasks are set as follows: to describe the principal characteristics of project work, to identify the types of projects and to analyse their benefits and pecularities, to analyse the project work organizing procedure.

The fundamental researches in the given field were carried out by such prominent scientists and methodologists as Legutke M., Thomas H., Heines S., Brumfit C., Hutchinson T., Fried-Booth D. and others.

Legutke and Thomas in their book “Process and Experience in the Language Classroom” suggest and analyse three types of projects: encounter projects, which enable students to make contact with native speakers; text projects which encourage students to use English language texts, either a range of them to research a topic or one text more intensively, for example, a play to read, discuss, dramatize, and rehearse; class correspondence projects which involve letters, audio cassettes, photographs, etc. as exchanges between learners in different countries.

Another explorer of the Project Work Method, Brumfit, in “Communicative Methodology in Language Teaching” provides the analysis of projects in which advanced adult students elect to work in groups to produce a radio programme about their own country. A range of topics, for example, ethnic groups, religion, education, are assigned to the groups, who research their topic and write and rehearse a script.

Hutchinson in “Introduction to Project Work” dwells upon a project on ‘Animals in Danger’ for secondary school students, in which they use knowledge from Science and Geography to research threatened species, write an article, and make a poster.

Fried-Booth in his book “Project Work” suggests a more teacher-directed example suitable for junior learners at an elementary level, in which they are asked to collect food labels or wrappings from tins, cartons, packets, etc. for a period of a week. These are used to create a wall display with a map of the world illustrated with the labels, which are attached to the relevant countries of origin and export with coloured threads and pins. The map is then used for oral practice and controlled writing.

Another scientist, Haines, in “Projects for the EFL Classroom” considers four types of project work, namely: informational and research projects, survey projects, production projects, and performance and organizational projects.

The theoretical value of the course paper is in the generalization and detailed analysis of the fundamental characteristics of project work, the difference between the types of project work and their effectiveness.

The practical value of the paper lies in the selection of various project work English teaching procedures.

Chapter I. Project Work in Teaching English

1.1 Characteristics of Project Work

A project is an extended piece of work on a particular topic where the content and the presentation are determined principally by the learners. The teacher or the textbook provides the topic, but the project writers themselves decide what they write and how they present it. This learner-centred characteristic of project work is vital, as we shall see when we turn now to consider the merits of project work. It is not always easy to introduce a new methodology, so we need to be sure that the effort is worthwhile. Students do not feel that English is a chore, but it is a means of communication and enjoyment. They can experiment with the language as something real, not as something that only appears in books. Project work captures better than any other activity the three principal elements of a communicative approach.

These are:

a) a concern for motivation, that is, how the learners relate to the task.

b) a concern for relevance, that is, how the learners relate to the language.

c) a concern for educational values, that is, how the language curriculum relates to the general educational development of the learner. [7,40]

A project is an extended task which usually integrates language skills through a number of activities. These activities combine in working towards an agreed goal and may include planning, gathering of information through reading, listening, interviewing, discussion of the information, problem solving, oral or written reporting, display, etc.

Learners' use of language as they negotiate plans, analyse, and discuss information and ideas is determined by genuine communicative needs. At the school level, project work encourages imagination and creativity, self-discipline and responsibility, collaboration, research and study skills, and cross-curricular work through exploitation of knowledge gained in other subjects. Successful use of project work will clearly be affected by such factors as availability of time, access to authentic materials, receptiveness of learners, the possibilities for learner training, and the administrative flexibility of institutional timetabling. [1,38]

Project work leads to purposeful language use because it requires personal involvement on the part of the students from the onset of a project, students, in consultation with their instructor, must decide what they will do and how they will do it, and this includes not only the content of the project, but also the language requirements. So from this point project work emerges as a practical methodology that puts into practice the fundamental principles of a communicative approach to language teaching. It can thus bring considerable benefits to our language classroom, like:

· Increased motivation - learners become personally involved in the project.

· All four skills, reading, writing, listening and speaking, are integrated.

· Autonomous learning is promoted as learners become more responsible for their own learning.

· There are learning outcomes -learners have an end product.

· Authentic tasks and therefore the language input are more authentic.

· Interpersonal relations are developed through working as a group.

· Content and methodology can be decided between the learners and the teacher and within the group themselves so it is more learner centred.

· Learners often get help from parents for project work thus involving the parent more in the child's learning. If the project is also displayed parents can see it at open days or when they pick the child up from the school.

· A break from routine and the chance to do something different.

· A context is established which balances the need for fluency and accuracy.[1,40]

It would be wrong to pretend that project work does not have its problems. Teachers are often afraid that the project classroom will be noisier than the traditional classroom and that this will disturb other classes in the school, but it does not have to be noisy. Students should be spending a lot of the time working quietly on their projects: reading, drawing, writing, and cutting and pasting. In these tasks, students will often need to discuss things and they may be moving around to get a pair of scissors or to consult a reference book, but this is not an excuse to make a lot of noise. If students are doing a survey in their class, for example, there will be a lot of moving around and talking. However, this kind of noise is a natural part of any productive activity. Indeed, it is useful to realize that the traditional classroom has quite a lot of noise in it, too. There is usually at least one person talking and there may be a tape recorder playing, possibly with the whole class doing a drill. There is no reason why cutting out a picture and sticking it in a project book should be any noisier than 30 or 40 students repeating a choral drill. The noise of the well-managed project classroom is the sound of creativity.

Project work is a different way of working and one that requires a different form of control. Students must take on some of the responsibility for managing their learning environment. Part of this responsibility is learning what kind of, and what level of noise is acceptable. When we introduce project work we also need to encourage and guide the learners towards working quietly and sensibly. [7,112]

This kind of work is time-consuming of course, it takes much longer to prepare, make, and present a project than it does to do more traditional activities. When we are already struggling to get through the syllabus or finish the textbook, we will probably feel that we do not have time to devote to project work, however good an activity it may be. There are two responses to this situation:

1. Not all project work needs to be done in class time. Obviously, if the project is a group task, most of it must be done in class, but a lot of projects are individual tasks. Projects about My Family, My House, etc. can be done at home.

2. When choosing to do project work we are making a choice in favour of the quality of the learning experience over the quantity. It is unfortunate that language teaching has tended to put most emphasis on quantity. And yet there is little evidence that quantity is really the crucial factor. What really matters in learning is the quality of the learning experience.

3. Project work provides rich learning experiences: rich in colour, movement, interaction and, most of all, involvement. The positive motivation that projects generate affects the students’ attitude to all the other aspects of the language programme. Learning grammar and vocabulary will appear more relevant because the students know they will need these things for their project work. [7,120]

The students will spend all their time speaking their mother tongue. This is true to a large extent. It is unlikely that most students will speak English while they are working on their project. However, rather than seeing this as a problem, we should consider its merits:

a) it is a natural way of working. It is a mistake to think of L1 (the mother tongue) and L2 (the language being learnt) as two completely separate domains. Learners in fact operate in both domains, constantly switching from one to the other, so it is perfectly natural for them to use L1 while working on a L2 product. As long as the final product is in English it does not matter if the work is done in L1.

b) project work can provide some good opportunities for realistic translation work. A lot of the source material for projects (leaflets, maps, interviews, texts from reference books, etc.) will be in the mother tongue. Using this material in a project provides useful translation activities.

c) there will be plenty of opportunities in other parts of the language course for learners to practice oral skills. Project work should be seen as a chance to practice that most difficult of skills, writing.

Some teachers are concerned that without the teacher’s firm control the weaker students will be lost and will not be able to cope. But not all students want or need the teacher’s constant supervision. By encouraging the more able students to work independently we are free to devote our time to those students who need it most. One group may have ‘finished’ the project after a couple of hours and say they have nothing to do than remind them that it is their responsibility to fill the time allocated to project work and discuss ways they could extend the work they have already completed. [11,237]

Assessment of project work is another difficult issue. This is not because project work is difficult to assess, but because assessment criteria and procedures vary from country to country. So there are two basic principles for assessing project work:

a) not just the language

The most obvious point to note about project work is that language is only a part of the total project. Consequently, it is not very appropriate to assess a project only on the basis of linguistic accuracy. Credit must be given for the overall impact of the project, the level of creativity it displays, the neatness and clarity of presentation, and most of all the effort that has gone into its production. There is nothing particularly unusual in this. It is normal practice in assessing creative writing to give marks for style and content, etc. Many education systems also require similar factors to be taken into account in the assessment of students’ oral performance in class. So a wide-ranging ‘profile’ kind of assessment that evaluates the whole project is needed.

b) not just mistakes

If at all possible, we should not correct mistakes on the final project itself, or at least not in ink. It goes against the whole spirit of project work. A project usually represents a lot of effort and is something that the students will probably want to keep. It is a shame to put red marks all over it. This draws attention to the things that are wrong about the project over the things that are good. On the other hand, students are more likely to take note of errors pointed out to them in project work because the project means much more to them than an ordinary piece of class work. There are two useful techniques to handle the errors:

• Encouraging the students to do a rough draft of their project first. Correcting this in their normal way. The students can then incorporate corrections in the final product.

• If errors occur in the final product, correcting in pencil or on a separate sheet of paper attached to the project. A good idea was suggested by a teacher in Spain to get students to provide a photocopy of their project. Corrections can then be put on the photocopy. But fundamentally, the most important thing to do about errors is to stop worrying about them. Projects are real communication. When we communicate, we do the best we can with what we know, and because we usually concentrate on getting the meaning right, errors in form will naturally occur. It is a normal part of using and learning a language. Students invest a lot of themselves in a project and so they will usually make every effort to do their best work. [13,106]

Project work provides an opportunity to develop creativity, imagination, enquiry, and self-expression, and the assessment of the project should allow for this.

Project work must rank as one of the most exciting teaching methodologies a teacher can use. It truly combines in practical form both the fundamental principles of a communicative approach to language teaching and the values of good education. It has the added virtue in this era of rapid change of being a long- established and well-tried method of teaching.

1.2 Types of Project Work

Project work involves multi-skill activities which focus on a theme of interest rather than specific language tasks. In project work, students work together to achieve a common purpose, a concrete outcome (e.g., a brochure, a written report, a bulletin board display, a video, an article for a school newspaper, etc). Haines identifies four types of projects:

1. Information and research projects which include such kinds of work as reports, displays, etc.

2. Survey projects which may also include displays, but more interviews, summaries, findings, etc.

3. Production projects which foresee the work with radio, television, video, wall newspapers, etc.

4. Performance/Organizational projects which are connected with parties, plays, drama, concerts, etc.[1,65]

What these different types of projects have in common is their emphasis on student involvement, collaboration, and responsibility. In this respect, project work is similar to the cooperative learning and task-oriented activities that are widely endorsed by educators interested in building communicative competence and purposeful language learning. However, it differs from such approaches, it typically requires students to work together over several days or weeks, both inside and outside the classroom, often in collaboration with speakers of the target language who are not normally part of the educational process.

Students in tourism, for example, might decide to generate a formal report comparing modes of transportation; those in hotel/restaurant management might develop travel itineraries. In both projects, students might create survey questionnaires, conduct interviews, compile, sort, analyze, and summarize survey data and prepare oral presentations or written reports to present their final product. In the process, they would use the target language in a variety of ways: they would talk to each other, read about the focal point of their project, write survey questionnaires, and listen carefully to those whom they interview. As a result, all of the skills they are trying to master would come into play in a natural way.

Let us consider, for example, the production of a travel brochure. To do this task, tourism students would first have to identify a destination, in their own country or abroad, and then contact tourist agencies for information about the location, including transportation, accommodations in all price ranges, museums and other points of interest, and maps of the region. They would then design their brochure by designating the intended audience, deciding on an appropriate length for their suggested itinerary, reviewing brochures for comparable sites, selecting illustrations, etc. Once the drafting begins, they can exchange material, evaluate it, and gradually improve it in the light of criteria they establish. Finally, they will put the brochure into production, and the outcome will be a finished product, an actual brochure in a promotional style. Projects allow students to use their imagination and the information they contain does not always have to be factual. [1,80]

One of the great benefits of project work is its adaptability. We can do projects on almost any topic. They can be factual or fantastic. Projects can, thus, help to develop the full range of the learners’ capabilities. Projects are often done in poster format, but students can also use their imagination to experiment with the form. It encourages a focus on fluency.

Each project is the result of a lot of hard work. The authors of the projects have found information about their topic, collected or drawn pictures, written down their ideas, and then put all the parts together to form a coherent presentation.

The projects are very creative in terms of both content and language. Each project is a unique piece of communication, created by the project writers themselves. This element of creativity makes project work a very personal experience. The students are writing about aspects of their own lives, and so they invest a lot of themselves in their project.

Project work is a highly adaptable methodology. It can be used at every level from absolute beginner to advanced. There is a wide range of possible project activities, and the range of possible topics is limitless.

Positive motivation is the key to successful language learning, and project work is particularly useful as a means of generating it.

Another point is that this work is a very active medium like a kind of structured playing. Students are not just receiving and producing words, they are:

• collecting information;

• drawing pictures, maps, diagrams, and charts;

• cutting out pictures;

• arranging texts and visuals;

• colouring;

• carrying out interviews and surveys;

• possibly making recordings, too.

Lastly, project work gives a clear sense of achievement. It enables all students to produce a worthwhile product. This feature of project work makes it particularly well suited to the mixed ability class, because students can work at their own pace and level. The brighter students can show what they know, unconstrained by the syllabus, while at the same time the slower learners can achieve something that they can take pride in, perhaps compensating for their lower language level by using more photos and drawings. [14,320]

A foreign language can often seem a remote and unreal thing. This inevitably has a negative effect on motivation, because the students do not see the language as relevant to their own lives. If learners are going to become real language users, they must learn that English is not only used for talking about British or American things, but can be used to talk about their own world.

Firstly, project work helps to integrate the foreign language into the network of the learner’s own communicative competence. It creates connections between the foreign language and the learner’s own world. It encourages the use of a wide range of communicative skills, enables learners to exploit other spheres of knowledge, and provides opportunities for them to write about the things that are important in their own lives.

Secondly, it helps to make the language more relevant to learners’ actual needs. When students use English to communicate with other English speakers, they will want, and be expected, to talk about aspects of their own lives – their house, their family, their town, etc. Project work thus enables students to rehearse the language and factual knowledge that will be of most value to them as language users.

Another important issue in language teaching is the relationship between language and culture. It is widely recognized that one of the most important benefits of learning a foreign language is the opportunity to learn about other cultures and English, as an international language, should not be just for talking about the ways of the English – speaking world, but also as a means of telling the world about one’s own culture. [16,157]

There is a growing awareness among language teachers that the process and content of the language class should contribute towards the general educational development of the learner. Project work is very much in tune with modern views about the purpose and nature of education:

1. There is the question of educational values. Most modern school curricula require all subjects to encourage initiative, independence, imagination, self- discipline, co-operation, and the development of useful research skills. Project work is a way of turning such general aims into practical classroom activity.

2. Cross-curricula approaches are encouraged. For language teaching this means that students should have the opportunity to use the knowledge they gain in other subjects in the English class.

So we can come to the conclusion that project work activities are very effective for the modern school curricula and should be used while studying.

1.3 Organizing Project Work

Although recommendations as to the best way to develop projects in the classroom vary, most are consistent with the eight fundamental steps. Though the focus is upon the collaborative task, the various steps offer opportunities to build on the students’ heightened awareness of the utility of the language by working directly on language in class. In short, language work arises naturally from the project itself, ‘developing cumulatively in response to a basic objective, namely, the project’ [2,57]. Strategically orchestrated lessons devoted to relevant elements of language capture students’ attention because they have immediate applicability to their project work.

Step I: Defining a theme.

In collaboration with students, we identify a theme that will amplify the students’ understanding of an aspect of their future work and provide relevant language practice. In the process, teachers will also build interest and commitment. By pooling information, ideas, and experiences through discussion, questioning, and negotiation, the students will achieve consensus on the task ahead.

Step II: Determining the final outcome.

We define the final outcome of the project (e.g., written report, brochure, debate, video) and its presentation (e.g., collective or individual). We agree on objectives for both content and language.

Step III: Structuring the project.

Collectively we determine the steps that the students must take to reach the final outcome and agree upon a time frame. Specifically, we identify the information that they will need and the steps they must take to obtain it (e.g., library research, letters, interviews, faxes). We consider the authentic materials that the students can consult to enhance the project (e.g., advertisements from English magazines, travel brochures, menus in English, videos, etc.). Decide on each student’s role and put the students into working groups. If they are not used to working together, they may need help in adapting to unsupervised collaboration. They may also be a little reluctant to speak English outside the classroom with strangers.

Step IV: Identifying language skills and strategies.

There are times, during project work, when students are especially receptive to language skills and strategy practice. We consider students’ skills and strategy needs and integrate lessons into the curriculum that best prepare students for the language demands associated with Steps V, VI, and VII.

1. We identify the language skills which students will need to gather information for their project (Step V) and strategies for gathering information. If students will secure information from aural input, we show them how to create a grid for systematic data collection to facilitate retrieval for comparison and analysis.

2. We determine the skills and strategies that students will need to compile information that may have been gathered from several sources and/or by several student groups (Step VI).

3. We identify the skills and strategies that students will need to present the final project to their peers, other classes, or the headmaster (Step VII). As they prepare their presentations, they may need to work on the language (written or spoken) of formal reporting.

Step V: Gathering information.

After students design instruments for data collection, we have them gather information inside and outside the classroom, individually, in pairs, or in groups. It is important that students ‘regard the tracking down and collecting of resources as an integral part of their involvement’ in the project.

Step VI: Compiling and analysing information.

Working in groups or as a whole class, students should compile information they have gathered, compare their findings, and decide how to organize them for efficient presentation. During this step, students may proofread each other’s work, cross-reference or verify it, and negotiate with each other for meaning.

Step VII: Presenting final product.

Students will present the outcome of their project work as a culminating activity. The manner of presentation will largely depend on the final form of the product. It may involve the screening of a video; the staging of a debate; the submission of an article to the school newspaper or a written report to the headmaster; or the presentation of a brochure to a local tourist agency or hotel.

Step VIII: Evaluating the project.

In this final phase of project work, students and the teacher reflect on the steps taken to accomplish their objectives and the language, communicative skills, and information they have acquired in the process. They can discuss the value of their experience and its relationship to future vocational needs. They can also identify aspects of the project which could be improved and/or enhanced in future attempts at project work.[2,105]

First of all, we should always consider the students’ long-term language needs. Though it may be difficult, we should try to identify the social and professional contexts that they will have to function in and to think of projects students can undertake that require them to use the language in a way that resembles their ultimate use.

Secondly, we should consider the linguistic skills that students will have to employ in these contexts. Projects that require practice in those skills would be most useful. If students have to manage a lot of fax traffic, the project’s subsidiary tasks should involve those types of activity.

Thirdly, consider what is feasible. One popular project involves querying travelers as they pass through an airport terminal or major train station.

Although an airport/train station is the ideal place to ask questions and to find English speakers to answer them, there may be no international airport or major train station at hand to use for this purpose. If this is the case, there is no point in insisting that students interview native speakers of English. At the same time, teachers should not abandon the idea of a project altogether if ideal circumstances are not available. Since most professional conversation in English is probably carried on among non-native speakers, students will benefit equally from projects that put them in touch with speakers of varieties of world English. In addition, there are numerous sources of material in English that can be obtained at no cost with a formal letter of request and then sifted, compared, and summarized. In other words, we should not give up simply because a pool of native speakers or authentic printed material is unavailable close to home.

Finally, we should do a lot of planning. Although the project approach requires student input and decision-making in the initial phase of project definition, the teacher’s understanding of the outcome and the steps needed to achieve project objectives is crucial. Therefore, before introducing the project, the teacher should identify topics of possible interest, the educational value of the outcome, corresponding activities, and the students’ material or cognitive needs in conducting the project. There are many schools where curricula demands, the lack of equipment, scheduling problems, issues of insurance, administrative rigidity, and the like preclude instructional innovations like project work.[6,240]

Incorporating project work into more traditional classrooms requires careful orchestration and planning. Students who are not used to functioning autonomously, who may even be accustomed to close control and monitoring, may find it hard to take control of their own activity. Therefore, we should ease them into it by planning cooperative, small group work beforehand.

Similarly, many teachers encounter resistance from school administrators when they challenge the status quo with the project approach. Traditional schools that are governed by strict curricula guidelines and systematic testing are frequently not the most receptive environments for project work. Some administrators, for example, may complain that the elaborate activities associated with project work do not prepare students for required exams. Yet, if the underlying objective of the educational process is to build the students’ ability to use the language fluently in novel situations, project work will carry them a lot closer to meeting that objective than more conventional work on grammar, vocabulary, and pronunciation.

Project work can only be effective when teachers relax control of their students temporarily and assume the role of guide or facilitator. The teacher can play an important role by diligently overseeing the multiple steps of project work, establishing guidelines, helping students make decisions, and providing instruction in the language when it is needed. Giving students freedom to immerse themselves in the project can lead to motivated and independent learners, but it requires a certain flexibility on the part of the instructor if students are to benefit maximally.

Chapter II. Examples of Project Work Activities

2.1 Project Work Activities for the Elementary Level

The Class Contract

l. Divide the class into pairs. Ask each pair to draw up two lists: what they expect of you and what they think you should expect of them. Give them about fifteen minutes for this. Meanwhile you make a list of what you expect of them and what you think they should expect of you.

2. Tell your students that you want to draw up a contract with them based on the expectations that they and you have just noted down. Divide the board into two columns: ‘(your name) Agrees to’ and ‘The class agrees to’. Appoint a class secretary to make a fair copy of what you are about to write on the board and give them a sheet of paper to write it on. Nobody else need write anything. Negotiate with the class, on the basis of what you and they wrote down, what they can expect of you and you are willing to abide by, and vice versa. Draw up an agreed wording on the board for the secretary to copy. When it is complete, you and all your students must sign the secretary's fair copy.

3. Take the fair copy of the contract. Make enough copies to give one to each student. Distribute the copies next lesson and stick the original on the classroom wall. If any new students join the class, invite them to read the contract and sign it. Give them a copy too.

4. At regular intervals, once a week in a one-month course, or beginning, mid and end of terms in a one-year course, hold a brief discussion with the class on how well everyone is abiding by the contract. If you are all doing well, give yourselves a round of applause. If not, discuss what is going wrong and what you might do about it. This might include discussion as to whether you are slipping or the demands of the contract are unrealistic.

David agrees to give motivating lessons, maintain a good relationship with the class, be honest and critical, respond to initiatives, attend regularly and be punctual, correct homework promptly and thoroughly and to speak English out of class.

The signature of the teacher

We agree to cooperate and participate

attend regularly and be punctual

to do homework thoroughly

to speak English in class all the time except for words

we don’t know

be honest and critical

he signature of the students

Symbol Shadows

1. Write the quotation by Rabrindinath Tagore “What you are you do not see, what you see is your shadow.” on the board. Discuss it briefly with your students. Then draw a symbolic representation of your own ‘shadow’ on the board - various symbols that in some way represent you and things/people that are important to you. When you have drawn your shadow explain the symbols to your students.

2. Ask them to draw their own shadows. When they have done that, if you have a small class, ask them one by one to explain their shadow to everyone else. If your class has more than around a dozen students, divide the class into groups of between six and a dozen to do the cams. If you remain in whole-class formation, make sure the explanations are directed towards everyone in the class, not just you. If you have groups, monitor them discreetly, again making sure the explanations are directed towards their colleagues rather than you.

3. As a follow-up task, either in class or for homework, ask your students to write up the explanation of their symbols.

Here is an example of shadows done by a student with her own explanation of the symbols:

It is a sort of box because I’m very closed in myself, and with a locker because I do not let everybody in. In it there is a book, a radio/tape recorder and a TV, it is mainly what I spend my days doing when I am not at school or studying. There are also faces of boys and girls: these are my friends, and they are in a little box apart because I do not reveal myself to them, I do not have as many close friends as I would like.

Beatriz

The Happiness Cake

1. Ask everyone to think for a moment about the ingredients for happiness. Tell everyone to imagine they are going to bake a happiness cake. What ingredients and what spices would they put in? Ask them to work alone and write down the ingredients and spices for their cake. Allow five minutes for this.

2. If you have a small class, ask each member in turn to tell the others about the ingredients and spices for their cake. You tell them your list last. If you have a larger class, divide it into groups of six to dozen, and get them to do the same. Monitor the groups and when they have finished, ask them to report back to the whole class. Again tell them your ingredients and spices last.

What Went Right? What Went Wrong?

1. Talk to your students about your own good and bad learning experience and the extent to which these correlated with good and bad relationships with your teachers.

2. Tell your students to draw two columns. In the first they are to list teachers they remember getting on well with and in the other those they got on badly with. Divide the class into groups of four or five and ask them to tell one another about these teachers and effect they had on their learning.

3. Bring the students back together as a whole class and ask them what they feel are the main things that contribute to a good relationship between students and their teacher. The most important thing is regular, honest communication, because everything else both depends on this and can be remedied through this. Your students may come up with other points but be sure to emphasis the importance of regular, honest communication.

Variation

As a follow up, either in class or for homework get your students to write about their positive and negative learning experience.

If a Table Could Speak

1. Draw an object, e.g. a table, on the board. Tell the students that your object is the starting point for a picture you would like the class to create and that you would like them to come up to the board one at a time and add more things to it. Tell them that they can draw absolutely anything except people and that quality of the drawing does not matter. The picture is finished when there are about a dozen items in it.

2. Put the chalk or board pen where everyone can reach it easily – make sure they know where it is. Then get out of the way and let them draw the picture.

3. When the picture is reasonably complete declare the picture ready. If your class has had to come out to the front, send them back to their usual places.

4. Divide the class into pairs. Ask the pairs to choose any two items. In the picture write a dialogue between them of about ten lines. Tell your students they must not mention the name of their items in the dialogue. For example, if it is a dialogue between the table and a plant, the plant must not say, ‘Hello, table. How are you today?’ but just, ‘Hello, how are you today?’ Give a time limit of fifteen minutes. First reaction to this task would usually be a gasp of shock, but they should quickly get used to the idea. Keep out of the way for about five minutes while they settle. Then be available to help with vocabulary, etc. If you are not needed, do not hover, just sit down out of the way. As they are finishing, go round and check they have not mentioned the names of the ‘speakers’ in their dialogue as this will ruin Step 5.

5. When they have finished, ask the pairs in turn to read aloud their dialogue, each partner taking a part. The others in the class must guess which item is talking to which. This phase is very good for making students read loud and clearly as colleagues will not otherwise understand.

2.2 Project Work Activities for the Intermediate Level

Magnet, Island or Bridge

1. If you have a magnet, show it to the class and check if they know what it is called. Otherwise, you may need to explain it in the next step. On the board draw three columns, heading them respectively ‘magnet’, ‘island’ and ‘bridge’. Divide your class into pairs and ask them to draw up a list of characteristics in the columns on the board.

2. Ask your students to think for a moment about the way they act in various social contexts, for example at parties, with colleagues, in the family – more like a magnet, an island or a bridge. Divide the class into groups to discuss the problem briefly.

3. Ask them, still in groups, to discuss which attitude – the magnet, the island or the bridge – is most conductive to a good working environment in class and what that implies in term of actual behaviour.

4. Discuss as a class the findings of the groups. They should feel that being a bridge is the most conductive and that it implies a spirit of co-operation, participating, helping others. At the same time a magnet may on occasions act as a catalyst to encourage shyer members of the class when/how a magnet might be a positive element in a class and when/how a negative one.

5. Extend the discussion to how bridges can be formed out of class. Draw up a list on the board.

6. Give your students a few minutes to discuss with those sitting near them which of these ideas they feel are most appropriate to them and how they intend to implement them. It is better in this phase to let pairs/groups form spontaneously than to impose them. Ask a few members of the class what conclusion they came to.

Encouraging Reading

1. Initiate an informal discussion on your student’s reading habits in their own language. Ask which of them are in the habit of reading regularly in English outside class. Ask what kind of things they read and where they get their reading material from.

2. Put it to the class that for most learners regular reading out of class is absolutely essential to reach an advanced language level – it is one of the best ways of expanding vocabulary and probably the only way to get a good sense of style. Tell them you are going to work with them to set up a framework that encourages them to read regularly.

3. The first hurdle is to find a source of suitable books. With the help of your students, write a list on the board of possible sources of books in English. Tell them to copy it into their notebooks. It will probably look like this:

a) public lending libraries;

b) school libraries;

c) bookshops;

d) each other.

Discuss with the class which of these sources is/are most readily available.

4. Arrange with your students for all to bring a book to class the lesson after next so that everyone can get an idea of what their colleagues are going to read.

5. When the class brings their books, ask each student to set a realistic target date to read their book by. Tell them that the date must be agreed with you. Draw up a class list of author/title/target date for all their books and fix this to the classroom wall.

6. As target dates are reached, check on progress, do not be 'heavy' if they do not achieve their targets but remind them that they are the ones who set the target dates and that you do expect them to finish soon.

7. As students finish their books, ask them to fill in information about the books they have read on a ‘book recommendation sheet’, which you van fix to the wall for your students to consult. It might look like this:

Recommended Reading

Author Title Interest Difficulty Comments Reader

For ‘Interest’ and ‘Difficulty’ it is best to use a scale, for example one to five, to indicate the degree of interest and difficulty.

Variation

The same broad principles apply to listening. Below is a list of possible sources for material:

a) English-speaking people that students meet

b) television programmes

c) films (original or subtitled), film clubs

d) videos

e) theatre

f ) radio

g) songs

h) spoken word cassettes

Discuss with your students which of these are available locally. Draw their attention to the help that images give in understanding and to the high level of concentration needed when listening, which is quickly tiring. Follow-ups for listening are more difficult to set up than for reading. Once again, in general encourage reflection. Here are possible headings for a ‘recommended listening sheet’ that you can fix to the classroom wall:

Culture Project

1. Initiate a discussion with your students about their interests. Ask them about how they might link those interests to their study of English. Put it to them that they could extend an interest or begin a new one by doing a project on some aspect of English-speaking culture. Tell them that they can choose anything they like within that, only that at the end of the project they must produce something to present to the others in the class - orally or in writing. This can be something quite modest but its purpose is simply to provide some kind of objective. If you get a reasonably positive response, go on to Step 2.

2. Tell them that the hardest part is often choosing the project. So give them copies of the handout given below:

Example topics for personal culture projects

1. History

a) A long period, e.g. the Elizabeth era, the Victorian era

b) A short period, e.g. the American Civil War, Henry VIII and the Reformation

c) An incident and the events surrounding it, e.g. the Spanish Armada, the Wall Street Crash

2. Geography

a) A country you do not know about where English is spoken, e.g. one of the Caribbean or Pacific islands

b) A region or state in an English-speaking country, e.g. Florida, Wales, Queensland

c) A city or town, e.g. Cambridge, Stratford-upon-Avon, Auckland

3. People and their work

a) Statesmen and women, e.g. Gandhi, Churchill, Lincoln

b) Scientists, e.g. Newton, Darwin, Einstein

c) Artists of all kinds, e.g. The Beatles, Constable, Blake, Jane Austen, Shaw

d) Entertainers, e.g. Charlie Chaplin, Fred Astaire, Marilyn Monroe

e) Individuals, e.g. Martin Luther King, Bede, Dr Johnson

4. Other areas

a) Traditions and customs, e.g. Pancake Day, Thanksgiving

b) The Royal Family

c) Political institutions

d) Castles, stately homes and gardens

e) Folk music

f) Food and cooking

g) Porcelain and pottery, e.g. Wedgwood, Royal Doulton

h) Sport

i) Ways of being, e.g. attitudes, norms, taboos, behaviours

Ask your students each to decide on their project to tell you next lesson.

3. Next lesson ask each student what their project is going to be about and make a note of it. If more than one wants to work on a particular area, suggest they work in a pair, but discourage more than two students working on one project. There are so many to choose from that it is a pity not to have a wide range. Agree a target date for completion of the project and presentation to the class - in a one-month course it will have to be near the end of the course, in a year-long course towards the end of the term you start the project in. Tell your students that you will ask them from time to time how their projects are going and will set aside some class time to discuss progress and to deal with any problems.

Variation

Mini-projects have great success, where the students identify some small thing about English-speaking culture they want to know about and have just one lesson in a library to find out. You accompany them to the library and help them find the materials they need. The next lesson they report back what they found. Among the mini-projects which may be suggested are: willow-pattern pottery, Shakespeare’s life, the historical King Arthur, prehistoric monuments in Britain, Elgar, Liverpool and child labour in Victorian England.

2.3 Project Work Activities for the Advanced Level

Taking the Plunge

1. Ask your class what they think are the main problems of being a more advanced learner. They usually talk about difficult vocabulary, complex structures and other language items. Accept these points but put it to them that there is often a much more fundamental problem, namely how they go about their learning. If any student raises any of the more fundamental areas outlined in the handout, use this as a direct springboard into the next step.

2. Give each student a copy of the following handout.

Being a good advanced learner

Many learners of English manage to reach a level where they can understand, speak and write for everyday purposes. Yet only a relatively small proportion of these people ever become genuinely advanced users of the language, though many make the attempt. As you are just beginning a course in more advanced English, it is important for you to be aware of what you need to do and how to go about it, so that you can make a success of your course.

You are going to read a short text, with a series of tasks to do as you read. This will provide an opportunity to reflect on your learning and, through your answers to the tasks, will give your teacher valuable information about you as a learner, so that he or she can give you greater guidance for the future.

Beyond spoon-feeding

In many language courses the teaching at lower levels tends to follow a pattern of what could be described as 'spoon-feeding' - the teacher chooses the elements of the language to teach (the food), plans how to present it (puts it onto a spoon) and teaches (feeds) the learners with it, as if they were children. However, just as children become progressively more independent and in due course have to assume full responsibility for themselves as adults, so learners of a language, as they advance, have to become more independent and assume greater responsibility for their own learning.

To be successful at an advanced level, you will have to commit yourself not only to attending classes but also to spending a substantial amount of time studying out of class. This should partly be directed by your teacher (homework and preparation) and partly through your own initiative.

A typical student with three to five hours of English classes per week should expect to spend about the same number of hours studying out of class - doing grammar exercises and writing tasks, learning vocabulary, reading extensively, and so on. The fewer hours you have with a teacher, the more you will have to work on your own. Without this kind of commitment you cannot expect to make a lot of progress.

1. How many hours of English classes do you have each week?

2. How many more hours can you commit to learning English each week?

It is easy to commit yourself to a theoretical number of hours per week, but unless you set aside particular days and times, you will keep finding you are too busy doing other things. So decide now which days and times you are going to dedicate to studying English.

3. In the light of your commitment, how much progress do you expect to make? In what areas (e.g. listening/speaking/reading/writing, accuracy/fluency)? Be specific about your objectives.

Ways of studying

Making good progress depends not only on how much time you spend but also how you go about studying. For example, how do you organise the things you want to learn?

4. Write about how you organise the notes you take in class and the things you want to learn when studying on your own.

5. What techniques do you use to memorise things?

6. When you are studying alone, you need good reference materials. What dictionaries, grammar books and other materials do you have?

The quantum leap

Ironically, one of the greatest problems that often arises among more advanced learners is the fact that they can already function in English for a lot of everyday purposes and, instead of extending their knowledge, go on just using what they already know. To be successful at an advanced level, thin is not enough. You have to make a ‘quantum leap’, in other words a significant jump towards something much more sophisticated and wide-ranging. You have to aim to function like a mature, well-educated native speaker of the language. This means that you need to be able to draw upon your experience of the world and to have a reasonable, though not specialist, knowledge of any subject you are speaking or writing about. The content is vitally important, because if this is too limited, your language will be correspondingly limited - you won't need and therefore won't use more advanced structures and vocabulary.

7. How old are you?

8. What areas do you feel you have some knowledge about?

9. In what areas do you feel you have very little knowledge?

There are three areas that contribute substantially to making the quantum leap and particularly to writing in a more sophisticated way: observation, imagination and thinking.

10. Do you consider yourself to be good at

a) observing

b) imagining

c) thinking

Explain your answers.

Good luck with your advanced course.

Ask them to read the text and answer the questions. Set a time limit of thirty minutes. Tell your students that you will want to collect the completed handouts in to read, but that you are interested in what they say, not in how correct the English is. With students that finish early, take the opportunity to speak to individuals and discuss some of their answers.

3. When they have finished, initiate a discussion about what they have read and written. Ask them if they feel they have learnt anything important that they perhaps hadn't thought about before. Encourage an exchange of views among the members of the class. Collect in the completed handouts.

4. Later, go through the handouts, noting down any points you want to use for feedback and any you want to keep for your own reference. Make comments on the handouts about the contents where you feel this would be helpful to the student but don't correct. In a follow-up lesson, preferably the lesson immediately following, go over any points that emerged from the handouts. In particular, you may want to draw attention to reference materials you would recommend.

Variation

In Step 3, after the students have completed their handouts, put them into groups of four to compare and discuss what they wrote. In particular, ask them to discuss the specific contexts where the quantum leap would be important and the sort of tasks that might involve the three areas of observing, imagining and thinking. This can be very valuable but you will need to set aside about twenty minutes extra.

Ups and Downs

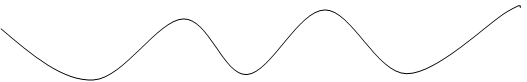

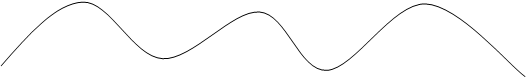

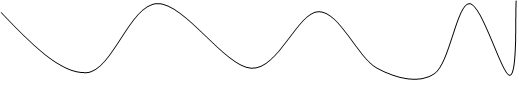

1. Initiate a discussion on ‘ups and downs’ – when we feel better or not so good. Draw the first to these graphs on the board, showing your own ups and downs. Explain your day rhythms with reference to the graphs.

|

Best Worst midnight 3 6 9 midday 15 18 21 midnight |

|

Best Worst Mon Tues Weds Thurs Fri Sat Sun am pm am pm am pm am pm am pm am pm am pm |

|

Best Worst J F M A M J J A S O N D |

Ask your students to copy the graphs and complete them with their own rhythms. When they are ready, ask them to explain their graphs to their colleagues. If your class has more than about twelve students, divide the class into groups of up to twelve for this phase; monitor them and when they have finished get the groups to report to the whole class the kinds of things they found.

English-Speaking Countries

1. Divide the class into pairs. Ask the pairs to draw up a list of English-speaking

speaking countries, that is to say, countries where English is an official language

or is widely spoken. Be available to help supply the names of countries in English.

2. On the board draw five columns and head them with the names of the main continents. Ask your students for the names of the countries they wrote down in Step 1 and write them in the appropriate column. When you have exhausted their lists, add any others you feel they should know. The main countries are:

Europe: Cyprus, Gibraltar, Ireland, Malta, The United Kingdom

Africa: Botswana, The Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Malawi, Namibia, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Swaziland, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe

Asia: Bangladesh, Brunei, Hong Kong, India, Malaysia, Pakistan, Singapore, Sri Lanka

Australia and the Pacific: Australia, Fiji, New Zealand, Tonga

The Americas: Canada, The United States, Belize, many of the Caribbean islands, including The Bahamas, Barbados, Dominica, Grenada, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, St Lucia, St Vincent, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, the Falkland Islands

3. Explain to the class that you want them to do a project on one of these countries but not on England or the United States. Tell the class to form groups of three or four. Let your students choose their partners, while making sure no individuals get left out. Ask each group to choose a country. Allow more than one group to work on the same country – they often use quite different approaches and present interestingly different work – but you may decide you want your students to do different work on as broad a range of countries as possible, in which case they should all choose different countries.

4. When your students have chosen their countries, ask each group, for your reference, to give you a piece of paper with the names of the members in their group and which country they are going to work on.

5. Establish with the class the following:

a) how much you want each student to contribute to the project;

b) the content - set an upper limit of one third dedicated to the general background (geography and history, currency, industries, etc.) and insist that the greater part should be dedicated to the use of the English language, e.g. the role of English, how it differs from standard British/American English, periodicals published in English, literature, etc. The possible areas of focus here vary considerably from country to country and you may need to discuss with each group those areas that would offer the most potential, e.g. the question of language variety is more appropriate where most or all of the population is English-speaking, the periodicals published in English are more relevant where English is one of the many languages used in the country;

c) the deadline by which the project must be handed in.

6. Discuss with your students what sources of information they are going to use. Students work mostly from five sources:

a) encyclopedia entries;

b) books;

c) newspaper and magazine articles;

d) computer programs;

e) information from embassies, high commissions and tourist offices.

You may be able to provide support from material you yourself possess - this is where it is useful to have a list of groups and their countries, so that you know who to give it to.

CONCLUSIONS

The objectives of the paper were to highlight the importance of the project work in teaching English, to discover how it influences the students during the educational process and if this type of work in the classroom helps to learn the language.

On the basis of the literary sources studied we can come to the following conclusions that project work has advantages like the increased motivation when learners become personally involved in the project; all four skills, reading, writing, listening and speaking, are integrated; autonomous learning is promoted as learners become more responsible for their own learning; there are learning outcomes -learners have an end product; authentic tasks and therefore the language input are more authentic; interpersonal relations are developed through working as a group; content and methodology can be decided between the learners and the teacher and within the group themselves so it is more learner-centred; learners often get help from parents for project work thus involving the parent more in the child's learning; if the project is also displayed parents can see it at open days or when they pick the child up from the school; a break from routine and the chance to do something different.

The disadvantages of project work are the noise which is made during the class, also projects are time-consuming and the students use their mother tongue too much, the weaker students are lost and not able to cope with the task and the assessment of projects is very difficult. However, every type of project can be held without any difficulties and so with every advantage possible.

The types of projects are information and research projects, survey projects, production projects and performance and organizational projects which can be performed differently as in reports, displays, wall newspapers, parties, plays, etc.

Though project work may not be the easiest instructional approach to implement, the potential pay-offs are many. At the very least, with the project approach, teachers can break with routine by spending a week or more doing something besides grammar drills and technical reading.

The organization of project work may seem difficult but if we do it step by step it should be easy. We should define a theme, determine the final outcome, structure the project, identify language skills and strategies, gather information, compile and analyse the information, present the final product and finally evaluate the project. Project work demands a lot of hard work from the teacher and the students, nevertheless, the final outcome is worth the effort.

Throughout the course paper we can see that project work has more positive sides than negative and is effective during the educational process. Students are likely to learn the language with the help of projects and have more fun.

To conclude, project work is effective, interesting, entertaining and should be used at the lesson.

LIST OF REFERENCES

1. Haines S. Projects for the EFL Classroom: Resource materials for teachers. – Walton-on-Thames: Nelson, 1991. – 108p.

2. Phillips D., Burwood S., Dunford H. Projects with Young Learners. – Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. – 160p.

3. Brumfit C. Communicative Methodology in Language Teaching. The Roles of Fluency and Accuracy. – Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991. – 500p.

4. Fried-Booth D. Project Work. – Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990. – 89p.

5. Hutchinson T. Introduction to Project Work. – Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996. – 400p.

6. Legutke M., Thomas H. Process and Experience in the Language Classroom. – Harlow: Longman, 1991. – 200p.

7. Phillips D., Burwood S., Dunford H. Projects with Young Learners. Resource Books for Teachers – Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. – 153p.

8. Ormrod J. F. Education Psychology: Developing Learners. – Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2000. – 627 p.

9. Emmer E. T., Evertson C. M., Worsham M. E. Classroom Management for Successful Teachers (4th edition). – Boston: Allyn & Bacon, 1997. – 288 p.

10. Brown H.D. Principles of Language Learning and Teaching (4th edition). – Englewood Cliffs NJ: Prentice Hall, 2000. – 320-355 p.

11. Finegan E. Language: Its Structure and Use (3rd edition). – Oxford: Heinemmann, 1999. – 158 p.

12. Estaire S., Zanon J. Planning Classwork. A task-based approach. – Oxford: Heinemmann, 1994. – 93p.

13. Lavery C. Focus on Britain Today. Cultural Studies for the Language Classroom. – London: Macmillan Publishers Ltd, 1993. – 122p.

14. Ribe R., Vidal N. Project Work. Step by Step. – Oxford: Heinmann, 1993. – 94p.

15. Wicks M. Imaginative Projects. A resource book of project work for young students. – Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. – 128p.

16. Çèìíÿÿ È. À., Ñàõàðîâà Ò. Å. Ïðîåêòíàÿ ìåòîäèêà îáó÷åíèÿ àíãëèéñêîìó ÿçûêó // Èíîñòðàííûå ÿçûêè â øêîëå., 1991. – ¹3 – Ñ.9-15.

17. Ïîëàò Å. Ñ. Ìåòîä ïðîåêòîâ íà óðîêàõ èíîñòðàííîãî ÿçûêà // Èíîñòðàííûå ÿçûêè â øêîëå., 2000. – ¹2 – Ñ.3-10 - ¹3 – Ñ.3-9.

18. Gray S. Communication through Projects. – Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994. – 350p.

19. Morris P. The Management of Projects. – London: Thomas Telford Services Ltd., 1994. – 450p.

20. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Project Work

A)

Day Rhythms

A)

Day Rhythms B)

Week Rhythms

B)

Week Rhythms C)

Year Rhythms

C)

Year Rhythms